In this blog post, I critically reflect on the implications of different adjectives commonly used to describe approaches to design thinking (e.g., user-centered, participatory, community-based). In so doing, I also make the case for revising how we conceptualize the first step in the design process for social innovation.

Recently I’ve come across several discussions (see here and here) highlighting words that should be banned from international development discourse, or at least used with greater awareness of how problematic they can be (perhaps “international development” should itself be on the list?).

Evidently there are some words that folks are tired of hearing — in part because those words carry negative connotations about what “development” entails (and by whom, for whom, and why), and in part because they are faddish jargon used “to signal cleverness or curry favour with the hegemons” (as Duncan Green put it).

I share some of these concerns when it comes to choosing the right word to describe my approach to design thinking. So, in the spirit of unpacking some of my own jargon and reflecting on the pros and cons of my word choice, I’ll run through some popular adjectives associated with design thinking and then leave you with the rationale for my preferred one.[i]

User or human-centered design

User-centered design or human-centered design emphasize putting the individuals who will be using a product or service at the center of the design process. This helps designers identify and respond to issues that users are anticipated to have with a design. These approaches emphasize the importance of observation and empathy as the starting points of the design process.

However, while centering the end-users is incredibly useful and results in better product or service design, the words “user” and “human” are singular and emphasize the individual rather than the collective.

Emphasizing the individual is appropriate for designing a better office chair or smartphone app, but perhaps less so for designing a better water treatment facility, textile manufacturing process, or training program for public health workers. In these latter cases, more different stakeholders’ perspectives are important to consider, including those that would be difficult for an outsider to imagine or empathize with in the absence of direct experience or extensive consultation.

This is an important reason why design thinkers turn to participatory approaches.

Participatory design

Participatory design emphasizes participation of the end-users in the design process. In other words, designers don’t just empathize with the end-users — as user/human-centered design emphasizes — they directly involve them by giving them opportunities for feedback and suggestions at every stage of the design process. This is especially important when designers are not personally familiar with the problem they are trying to address.

However, although a participatory approach to design (or development) is an enormous leap beyond top-down, expert-controlled, exclusionary approaches, the word “participatory” implies that the design process is one in which designers control the design space and invite or allow end-users to participate (see Mansuri and Rao for further problematization of “participation”).

This might be OK for scenarios like inviting potential end-users to provide feedback to design a new, better consumer product or service that they may or may not choose to purchase later (and they don’t really need anyway). But in the context of designing a solution to a sustainable development challenge (e.g., urban food deserts; contaminated drinking water; low literacy rates; etc.), getting the solution right really matters for people’s lives and livelihoods. In such contexts, the people impacted by the design should have some authority and power in the design and decision-making process.

Indeed, too often experts believe that if others reject their Big Idea, it’s because they don’t yet understand its value. With this line of thinking, the course of action would be outreach and education about the Big Idea’s value (e.g., “demos”).

But suppose the rejection of the Big Idea is not due to a lack of understanding on the part of the end-users but rather a lack of understanding on the part of the designers? Perhaps that Big Idea has significant shortcomings that are meaningful within the cultural, institutional, economic, and environmental context of the community. In other words: perhaps it’s not an issue of education or communication but rather relevance.

Instead of trying to change an entire community to fit with a design, designers should work with the community to develop designs that are adapted to — and desired by — the community (see for example the literature on “appropriate technology”).

Community-based design emphasizes this kind of community orientation and prioritization.

Community-centered and community-driven design

To me, the core distinction between community-centered and community-driven — both of which might be considered community-based — is that community-driven approaches are those that are initiated and fully “owned” by the community. Outside experts might serve as facilitators/mentors who provide tools, workshops, etc. (read Norman and Spencer’s discussion of community-driven design here). Community-centered design processes are initiated and/or managed by people outside the community who “center” the community in the design process and outcome.

In either case, placing emphasis on the community rather than the individual matters for social innovations that affect and involve many different stakeholders. For this reason, I favor these design adjectives over “user-centered” or “human-centered.”

However, one potential drawback to using the word “community” is that it can suggest that a community’s boundaries are well-defined and stable when in fact they are fuzzy and dynamic. To avoid this methodologically and politically thorny issue of defining who is and who isn’t a member of a community, an alternative word can be used: collaborative.

Collaborative design

On one hand, clearly it is important for community outsiders to respect the autonomy of a community; thus, it matters to know who is and isn’t a community member. On the other hand, I believe effective — and humanizing — collaboration avoids “us” and “them” frameworks. Therefore, a balance must be found between acknowledging our respective positionalities and building authentic partnerships to achieve a shared goal.

Again, this is why I favor the adjective “collaborative” rather than “community-based” for describing my approach to design thinking for social innovation. The general term “collaborative design” avoids reinforcing preconceived power dynamics about who is and isn’t an expert. It also avoids connotations of scale and issues of defining community boundaries.

Instead, it emphasizes that good design may need the input of a wide range of stakeholders with varying kinds of expertise and experience. Moreover, in true collaborative spirit, power is shared. Sharing power requires more than the powerful group giving space for others to voice their perspectives: sharing power means sharing decision-making power.

In addition to these considerations, I also believe that we all have something to learn from each other. To me, the word “collaboration” implies an egalitarian relationship based upon reciprocity and mutual accountability. Forming a team to work together based around such collaborative values sets a positive and respectful tone for everyone involved. Ideally, everyone will feel like they have some “skin in the game” (more on this below).

From human-centered to collaborative

Coming back around to why terminology matters: the words we use to describe a process impact how we think about and engage in it.

Human-centered design thinking is usually described as involving five steps. These steps — which are overlapping and cyclical rather than discrete and linear — are typically listed as: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test.

Note that by using the word “empathize,” we’ve already placed the end-user as outside of the design process. This is not to say that empathy is unimportant (it’s actually very important in design thinking and in life!). Rather it is to highlight that the framing of the process in this way implies something about the social roles of those involved.

Of course, not all design processes mention “empathize.” Sometimes the process begins with defining the problem without any explicit mention of how this happens or who is involved. (Incidentally, there are many tools to help with problem definition that are beyond the scope of this blog post — but one tool that can help is to use the “5 Whys” approach, as explained by Eric Ries, an entrepreneur-in-residence at Harvard’s Business School, to identify “the human causes of technical problems.”)

Now, suppose instead of starting the design process by empathizing with end-users or defining the problem, design facilitators begin by convening the collaborators?

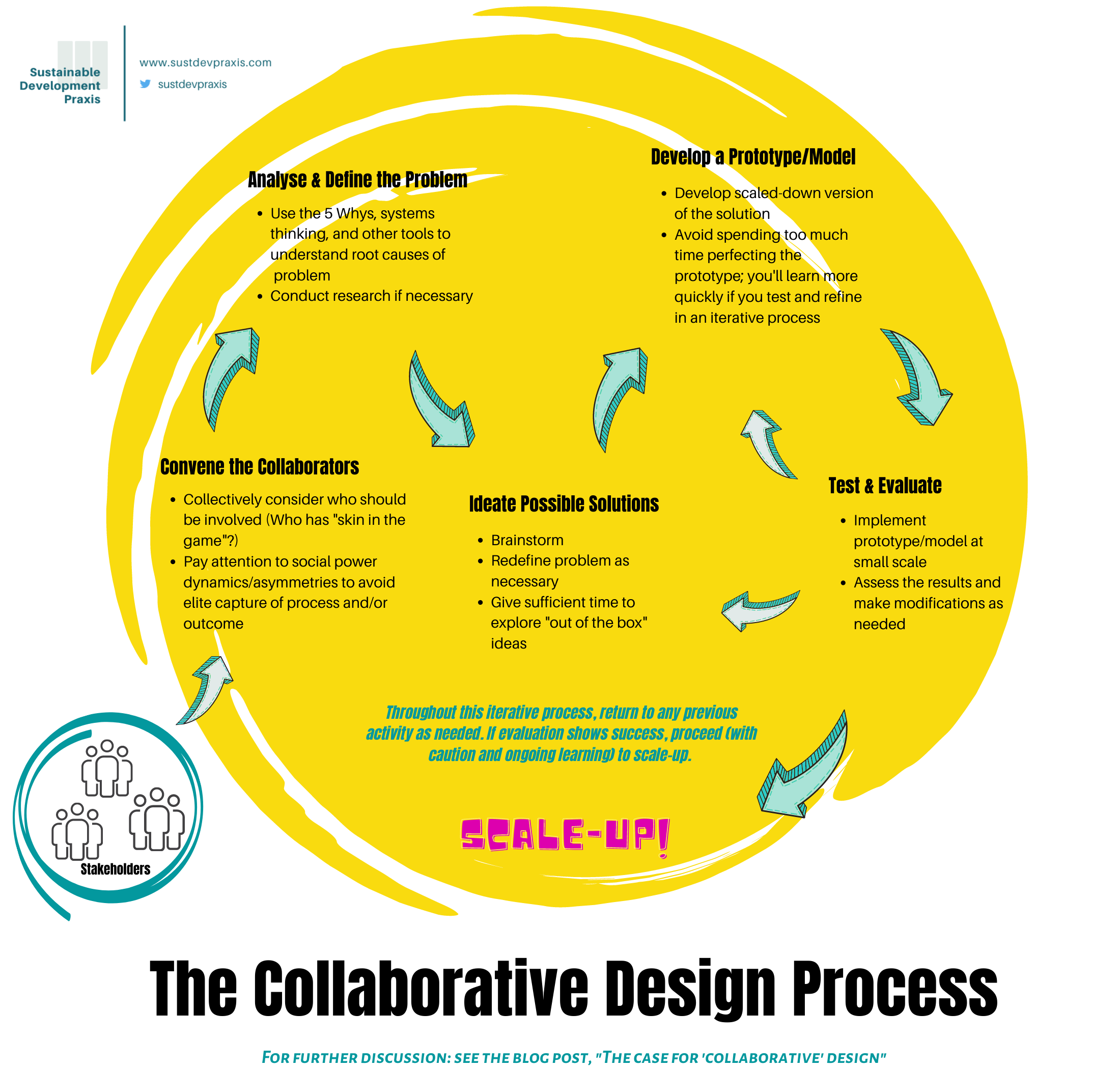

In that case, the basic collaborative design process can be reconceptualized as shown in the figure, “The Collaborative Design Process.” Notice that this figure does not indicate a distinction between designers and participants or users.

Indeed, more broadly speaking, design thinking aims to shift how people approach problem-solving:

“design thinking is about getting someone — yourself or your team — to actively look beyond that first idea, and break their attachment to and bias in their ownership of ideas. It’s about opening up space to have those discussions and explore.”

Kate Conrick (UX Collective, 2020)

Instead of believing that solutions only come from certain sources, we need to recognize that insights can come from many different sources. In fact, it’s through the incorporation of these diverse perspectives that the transformative potential of design thinking is unlocked.

“Skin in the game”: Linking design and implementation for efficacy and accountability

Before concluding this reflection on word choice, I want to emphasize that I am not arguing that these other adjectives should be discarded. Quite the contrary, actually. I’m arguing for critical reflection about our processes so that we select the one that is most appropriate. There are times and places where each of the different approaches conveyed through these different terms could be effectively utilized to advance sustainable development.

For example, MIT D-Lab has a great way of framing some of these considerations through their guiding principles:

– Use inclusive practices when designing FOR people living in poverty

– Engage in effective co-creation when designing WITH people living in poverty

– Build confidence and capacity to promote design BY people living in poverty

MIT D-Lab

The third guiding principle reflects one of the most important outcomes that should emerge from collaborative design thinking. As I’ve stated elsewhere regarding my approach to collaboration:

“My modus operandi is two-fold: ‘collaboration as capacity building’ and ‘capacity building through collaboration.’ This means that everyone involved in social innovation is a learner — and everyone should feel they have some ‘skin in the game.’ There’s no place for either arrogance or detachment when the stakes involve real people’s lives and dreams.”

I’ve since learned that Nassim Nicholas Taleb wrote a book called Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life (2018). In this book, Taleb argues that those who make recommendations should also bear consequences for the outcomes of their advice. That’s having “skin in the game.”

In a similar vein (and decades before Taleb’s book), Steve Jobs critiqued the typical “consultant” as missing out on deep learning. With brevity and eloquence — as well as humor — he argued that we learn the most by being involved not only in making recommendations but in implementing them (see this short video clip). In other words, we learn better when we have some ownership and responsibility for the consequences of our ideas.

This is an idea that is fundamentally at the core of all entrepreneurial ventures. The success and failure of a business start-up is borne by those calling the shots.

With that said, collaborations are subject to the effects of social power dynamics. Collaborators (and particularly facilitators) need to pay attention to existing social power asymmetries among the stakeholders. This includes using a justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion lens for convening the stakeholders but also throughout the design process to avoid elite capture of the process and/or outcomes. After all, it is likely that elite stakeholders not only have “skin in the game” — but also the power to ignore the ways in which others do too.

Towards a collaborative design praxis

Let me conclude by saying that my philosophy of praxis (iterative learning by doing + critical reflection) aligns with the notion that those involved in designing social innovations should also be involved in implementing or using them.

In practice what this means is that if you ever find yourself designing something without any input of those who are going to be involved in (or affected by) implementation, then stop. Stop and rethink who should be involved because not only do you not have skin in the game: you haven’t even engaged with those who do. That simple consideration will go a long way towards identifying which stakeholders should be convened in step one of a collaborative design process. (There are also plenty of tools to help and firms specializing in facilitating these kinds of collaborative design processes; for a list of co-creation toolkits, see here).

Through such collaborative processes, we all improve our capacity for effective design thinking. This means that we collaborators will be better able to apply our skills to refine social innovations over time and address other challenges that our communities face. That’s really the path towards sustainable “sustainable development.”

And what about those “hegemons”? Well, collaborative design or co-creation and co-design don’t have to be words used only to please the hegemonic powers-that-be. We can independently wield these terms ourselves to guide our own design processes for social innovation.

Endnotes

[i] Well, preferred at this time. Words are only useful insofar as they convey what we mean them to. As critics might say, the meanings I’ve assigned to these words do not necessarily reflect the ways that all others might interpret them — or will come to interpret them in 5, 10, or 100 years.